Machine Learning for Hackers Chapter 2, Part 1: Summary stats and density estimators

Chapter 2 of MLFH summarizes techniques for exploring your data: determining data types, computing quantiles and other summary statistics, and plotting simple exploratory graphics. I’m not going to replicate it in its entirety; I’m just going to hit some of the more involved or interesting parts. The IPython notebook I created for this chapter, which lives here, contains more code than I’ll present on the blog.

This part’s highlights:

- Pandas objects, as we’ve seen before, have methods that provide simple summary statistics.

- The plotting methods in Pandas let you pass parameters to the Matplotlib functions they call. I’ll use this feature to mess around with histogram bins.

- The

gaussian_kde(kernel density estimator) function inscipy.stats.kdeprovides density estimates similar to R’sdensityfunction for Gaussian kernels. Thekdensityfunction, instatsmodels.nonparametric.kdeprovides that and other kernels, but given the state ofstatsmodels‘ documentation, you would probably only find this function by accident. It’s also substantially slower thangaussian_kdeon large data. *[Not quite so! See update at the end.]

Height and weight data

The data analyzed in this chapter are the sexes, heights and weights, of

10,000 people. The raw file is a CSV that I import using read_table in Pandas:

heights_weights =

read_table('data/01_heights_weights_genders.csv', sep = ',', header = 0)

Inspecting the data with head,

print heights_weights.head(10)

gives us:

Gender Height Weight

0 Male 73.847017 241.893563

1 Male 68.781904 162.310473

2 Male 74.110105 212.740856

3 Male 71.730978 220.042470

4 Male 69.881796 206.349801

5 Male 67.253016 152.212156

6 Male 68.785081 183.927889

7 Male 68.348516 167.971110

8 Male 67.018950 175.929440

9 Male 63.456494 156.399676

So it looks like heights are in inches, and weights are in pounds. It also looks like the dataset is evenly split between men and women, since

heights_weights.groupby('Gender')['Gender'].count()

results in:

Gender

Female 5000

Male 5000

The data are simple, clean, and appear to have imported correctly. So, we can start looking at some simple summaries.

Numeric summaries, especially quantiles

The first part of Chapter 2 covers the basic summary statistics: means, medians, variances, and quantiles. The authors hand-roll the mean, median, and variance functions to see how each is calculated. All of these methods are available as methods to Pandas series, or as NumPy functions (which are typically what’s called by equivalent Pandas methods).

The describe method of Pandas series and data frames, which we saw in

Part 3 of Chapter 1, gives summary statistics. The summary stats for

the height variable are:

heights = heights_weights['Height']

heights.describe()

count 10000.000000

mean 66.367560

std 3.847528

min 54.263133

25% 63.505620

50% 66.318070

75% 69.174262

max 78.998742

The heights all lay within a reasonable range, with no apparent outliers

from bad data. The default quantile range in describe is 50%, so we

get the 75th and 25th percentiles. This can be changed with the

percentile_width argument; for example, percentile_width = 90 would

give the 95th and 5th percentiles.

There doesn’t seem to be a direct analog to R’s range function, which

calculates the difference between the maximum and minimum value of a

vector, nor for the quantile, which can calculate the quantiles at any

given a series of probabilities. These are easy enough to replicate though.

Note: Nathaniel Smith, in comments, points out that R’s

rangefunction doesn’t do this either, but just returns the min and max of a vector. There is a function for this in NumPy, though: themy_rangefunction below gives the same result as wouldnp.ptp(heights.values).ptpis the “peak-to-peak” (min-to-max) function.

Range is trivial:

def my_range(s):

'''

Difference between the max and min of an array or Series

'''

return s.max() - s.min()

Calling this, we get a range of 78.99 − 54.26 = 24.63 inches.

Next, a quantiles function to mimic R’s. We can just make a wrapper

around the quantile method, mapping it along a sequence of provided probabilities.

def my_quantiles(s, prob = (0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0)):

'''

Calculate quantiles of a series.

Parameters:

-----------

s : a pandas Series

prob : a tuple (or other iterable) of probabilities at

which to compute quantiles. Must be an iterable,

even for a single probability (e.g. prob = (0.50,)

not prob = 0.50).

Returns:

--------

A pandas series with the probabilities as an index.

'''

q = [s.quantile(p) for p in prob]

return Series(q, index = prob)

Note that the default argument gives quartiles. We can get deciles by calling:

print my_quantiles(heights, prob = arange(0, 1.1, 0.1))

which spits out:

0.0 54.263133

0.1 61.412701

0.2 62.859007

0.3 64.072407

0.4 65.194221

0.5 66.318070

0.6 67.435374

0.7 68.558072

0.8 69.811620

0.9 71.472149

1.0 78.998742

Note: the

quantilesfunction I’ve written is a little awkward when dealing with a single quantile. Because the list comprehension that computes the qunatiles requires that theprobargument be an iterable, you would have to pass a list, tuple, array or other iterable with a single value. You can’t just pass it a float. I’ve hit this issue a few times writing Python functions–where it’s difficult to make code robust to both iterable and singleton arguments. If anyone has tips on this (should I really be doing type checking?), I’d be thrilled to hear them.

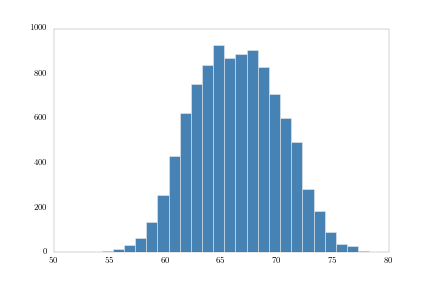

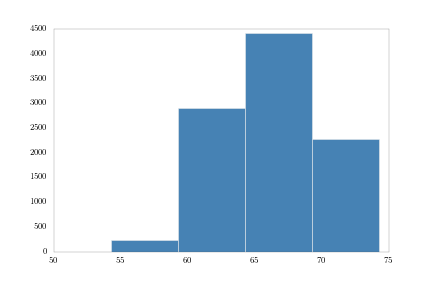

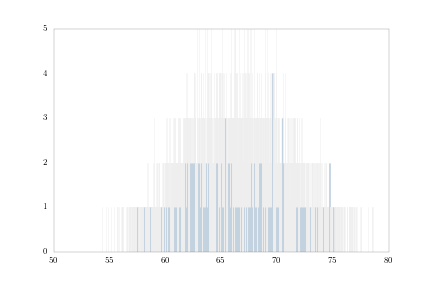

Histograms

Next the authors mess around with histograms and density plots to explore the distribution of the data. Noting that different bin sizes for histograms can affect how we perceive the data’s distribution, they plot histograms for a few different bin widths.

In Matplotlib, bins are not specified by their width, as is possible ggplot. We can either give Matplotlib the number of bins we want it to plot, or specify the actual bin-edge locations. It’s not difficult to translate a desired bin width into either one of these types of argument. I’ll provide the sequence of bins.

First, 1-inch bins:

bins1 = np.arange(heights.min(), heights.max(), 1.0)

heights.hist(bins = bins1, fc = 'steelblue')

Note how I’m using the Pandas hist method, which, using a **kwargs

argument, can pass parameters to the Matplotlib plotting functions.

Next, 5-inch bins:

bins5 = np.arange(heights.min(), heights.max(), 5.)

heights.hist(bins = bins5, fc = 'steelblue')

And finally, 0.001-inch bins:

bins001 = np.arange(heights.min(), heights.max(), .001)

heights.hist(bins = bins001, fc = 'steelblue')

plt.savefig('height_hist_bins001.png')

These all match the figures in the book, so I’m probably doing it right.

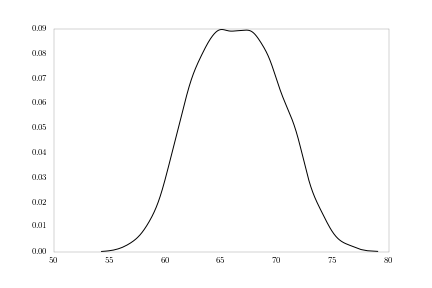

Kernel density estimators in SciPy and statsmodels

R’s density function computes kernel density estimates. The default

kernel is Gaussian, but you can also use Epanechnikov, rectangular,

triangular, biweight, cosine kernels.

In Python, it looks like you have two options for kernel density. The

first is gaussian_kde from the scipy.stats.kde module. This provides

a Gaussian kernel density estimate only. The other is kdensity in the

statsmodels.nonparametric.kde module, which provides alternative

kernels similar to R.

I actually wasn’t aware of the kdensity function for a while, until I

stumbled upon a mention of it on a mailing list archive. I couldn’t find

it in the statsmodels documentation. Statsmodels, generally, seems

to have a lot of undocumented functionality; not surprising for a young,

rapidly-expanding project.

Playing with both functions, I found some pros and cons for each.

Obviously kdensity provides an option of kernels, whereas

gaussian_kde does not. kdensity also generates simpler output than

gaussian_kde. kdensity provides a tuple of two arrays–the grid of

points at which the density was estimated, and the estimated density of

those points. gaussian_kde provides an object that you have to

evaluate on a set of points to get an array of estimated densities. So

essentially, you’re calling it twice, and I don’t see much point to that redundancy.

On the other hand kdensity gets much slower than gaussian_kde as

the number of points increases. For the 10,000 points in the = heights

array, gaussian_kde took about 3.3 seconds to output the array of

estimated densities. kdensity wasn’t finished after several minutes. I

haven’t looked carefully at the source code of the two functions, but I

assume kdensity‘s problem is that at some point it creates a temporary

NxN array, which for N = 10,000 is going to gum things up. Setting

the gridsize argument in kdensity to something even as large as

5000, cuts the size of the temporary array in half, and reduces the

running time to about 3 seconds.

This is probably worth exploring in a future post. In the meantime, I’m

going stick with gaussian_kde and plot some densities.

Note: See the update below. I’ve

updated the IPython notebook for this chapter to use Statsmodels’

KDE class instead of SciPy.]

First, heights:

density = kde.gaussian_kde(heights.values)

fig = plt.figure()

plt.plot(np.sort(heights.values),

density(np.sort(heights.values)))

The sorting of the heights array is to make the lines connect nicely.

Otherwise, the lines will connect from point-to-point in the order they

occur in the array; we want the density curve to connect points left-to-right.

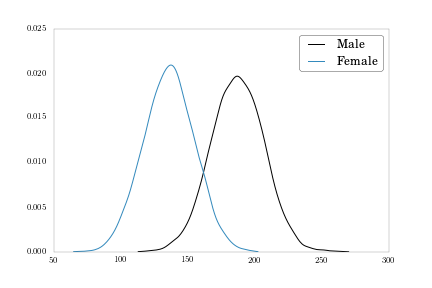

Notice the slight bi-modality in the figure. What we’re likely seeing is a mixture of male and female distributions. We can plot those separately.

# Pull out male and female heights as arrays over which to compute densities

heights_m = heights[heights_weights['Gender'] == 'Male'].values

heights_f = heights[heights_weights['Gender'] == 'Female'].values

density_m = kde.gaussian_kde(heights_m)

density_f = kde.gaussian_kde(heights_f)

fig = plt.figure()

plt.plot(np.sort(heights_m), density_m(np.sort(heights_m)), label = 'Male')

plt.plot(np.sort(heights_f), density_f(np.sort(heights_f)), label = 'Female')

plt.legend()

We also have a weight variable we can plot.

weights_m = heights_weights[heights_weights['Gender'] == 'Male']['Weight'].values

weights_f = heights_weights[heights_weights['Gender'] == 'Female']['Weight'].values

density_m = kde.gaussian_kde(weights_m)

density_f = kde.gaussian_kde(weights_f)

fig = plt.figure()

plt.plot(np.sort(weights_m), density_m(np.sort(weights_m)), label = 'Male')

plt.plot(np.sort(weights_f), density_f(np.sort(weights_f)), label = 'Female')

plt.legend()

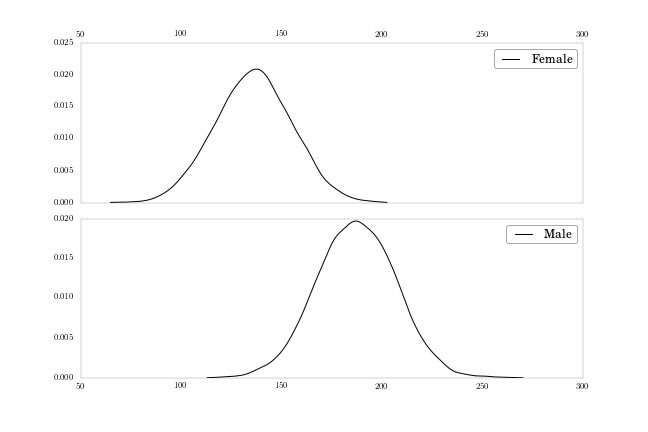

To finish up, let’s move each density plot to its own subplot, to match Figure 2-11 on page 51.

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows = 2, ncols = 1, sharex = True, figsize = (9, 6))

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace = 0.1)

axes[0].plot(np.sort(weights_f), density_f(np.sort(weights_f)),

label = 'Female')

axes[0].xaxis.tick_top()

axes[0].legend()

axes[1].plot(np.sort(weights_m), density_m(np.sort(weights_m)),

label = 'Male')

axes[1].legend()

Here I’m using the subplots function, same as in Part 5 of Chapter

1, and sharing the x-axis to make clear the difference between the

distributions’ central tendencies.

Conclusion

I’ll wrap up Chapter 2 in the next post, where I’ll look at lowess smoothing in Statsmodels, and get a little taste of logistic regression.

Update!

Statsmodels honcho skipper seabold sets me straight in the comments.

While the kdensity function is slow, statsmodels has an implementation

which uses Fast Fourier Transforms for Gaussian kernels and is

substantially faster than Scipy’s gaussian_kde.

For the heights array:

# Create a KDE object

heights_kde = sm.nonparametric.kde.KDE(heights.values)

# Estimate the density by fitting the object (default Gaussian kernel via FFT)

heights_kde.fit()

We can then plot this vector of estimated densities,

heights_kde.density against the points in heights_kde.support.

I’ve updated the IPython notebook for this chapter to use Statsmodels’ KDE throughout, so check it out for more detail.

Comments